Found Object Art

“An object—often utilitarian, manufactured, or naturally occurring—that was not originally designed for an artistic purpose, but has been repurposed in an artistic context.” – Museum of Modern Art

Marcel Duchamps Fountain is often sited as one of the first examples of ready-made art masquerading as found-object sculpture.

Fountain (Buddha) by Sherrie Levine is an homage to Duchamp’s renowned readymade, the Fountain. Levine turns his gesture back into an “art object” by elevating its materiality and finish.

Pedro Meier’s found object sculpture Futuristic Architecture (2014), made from iron wire, wood, white paint, and found objects.

Critics treated Tracey Emin's My Bed as a farce, claiming anyone could exhibit an unmade bed. To these claims Emin retorted, "Well, they didn't, did they?"

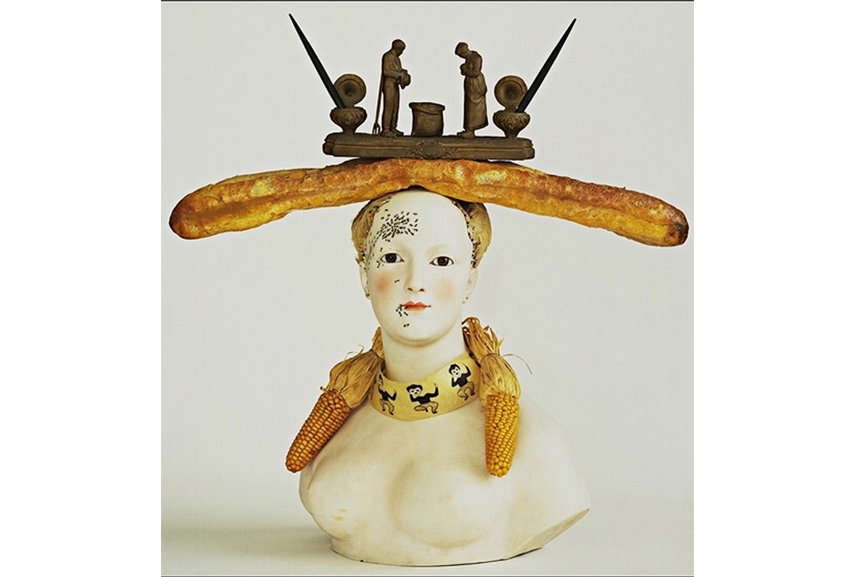

Salvador Dali's Retrospective Bust of a Woman.

Creating a taxonomy of art movements is a fraught effort, but the one above is as good a definition as any (and, coming from MOMA, presumptively and safely authoritative.) However, it does beg a tough question: what constitutes an artistic context? Does it require that the artist claims the object to be art? Does it require that the object be shown in an art space — a gallery, museum or exhibition of some kind? I say no to both.

What accounts for our need to classify artwork anyway? Does slotting art objects into these categories actually interfere with the viewers’ ability to apprehend the work on the level of self-expression that it was made?

When Duchamp hung the toilet on the gallery wall, he claimed that it was art because he, an artist, called it art. He said: “…an ordinary object could be elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of the artist.” This is an assertion that art is not about aesthetics or beauty or even emotion. It is about ideas. Since most people who go to museums or galleries disagreed, often vociferously, the split between the art world and the average human widened. It still remains difficult for some people to find anything appealing about, for example, Carl Andre’s unadorned bricks on the floor. A case can be made that the claim to high art that this kind of work makes could only have been made by the seriously self-regarding white men who made it. But I digress…

Of course, much of the art that uses found objects is unquestionably aesthetically appealing. Meret Oppenheim’s beguiling fur-covered dishware and cutlery are both beautiful and create a discussion around the value of domestic — women’s — work. And there are many many others.

Over the past hundred years, many threads have spun off the found object spool: Dada in the post-World War I era of disillusionment and political ferment; Assemblage (e.g. Robert Rauschenberg’s combines); Ready-made (the Duchamp contribution); environmental or land art, like the use or manipulation of natural land forms (e.g. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty;) and trash art, which rejects the culture of consumerism by using discarded and recycled material.

But I would like to make a claim for the foundational importance of the so-called vernacular artists, particularly those of the American South and other rural cultures. Among my favorites are Lonnie Holley, Thornton Dial, Ronald Lockett, Mary Proctor, Henry Speller, Jimmie Lee Sudduth, Mose Tolliver, and Purvis Young. You can see the work of a much larger group and read what they say about their impulse to make art, through the work of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

These artists lived primarily in poverty in the deep south. They did not make an aesthetic or intellectual choice to work with found objects; they did so because they had no access to expensive art supplies or even awareness of the art world. They used the materials they could find — discarded wood, machine parts, agricultural detritus, old clothes, and old house paint — to express what they felt. There is a deep strain of religious faith that runs through some of their work. When first approached by art collectors who saw the work as they drove by, most of them had never thought of themselves as artists. And yet, their work has been displayed in ever-growing installations outside their homes to larger audiences.

The work of these artists is deeply emotional, joyful, and totally honest, both for the artist and the viewer. The FOUND project, made collectively by community members from materials that surround them, can reflect that same spirit of openness, honesty, and joy.

You can see work in this exhibition, Called to Create: Black Artists of the American South, through the end of 2023 at the National Gallery of Art.

–written by Ellyn Weiss

ellynweiss.com

Bessie Harvey, Jezebel, 1987

Hannah Black, Transitional Object 5, 6, 2017

Hawkins Bolden, Untitled, 1985

Joe Light, Jewelry Mountain, 1987

Joe Minter, Four Hundred Years of Free Labor, 1995

Precious Okoyomon, A Drop of Sun Under The Earth, 2019

Ronald Lockett, Timothy, 1995

Ser Serpas, Conjoining fabricated excesses literal end to a mean, 2021

Thorton Dial, Test Chair (Remembering Bessie Harvey), 1995